Corporate Tax Filing and Planning Strategies for the Canadian Small Business Owner

Introduction

Incorporated businesses in Canada enjoy many tax benefits—if small business owners know the strategies to take advantage of those benefits. The key is finding ways to minimize your tax burden and maximize your after-tax income. Incorporated businesses are uniquely positioned to achieve both goals.

The variety of laws and regulations can make corporate tax filing and planning feel like a challenge. It doesn’t need to be, though. This guide explores everything you need to know about taxes and your small business.

Download a PDF version of this guide by filling out this form, or keep scrolling to learn more.

A Brief Overview of Corporate Tax vs. Personal Income Tax

Corporate tax refers to the portion of an incorporated Canadian company's profits that it pays to the local, provincial, or federal Canadian government and is considered a business expense (cash outflow). Other types of business structures, including sole proprietorships and partnerships, pay the personal income tax rate on their business income.

One of the biggest benefits of incorporating a business is lower tax rates. A business registered as a Canadian-controlled private corporation (CCPC) can take advantage of the small business tax deduction and pay a lower federal tax rate on the first $500,000 of its active business income or the money made from the business.

Any CCPC that holds more than $50,000 in passive investment income, such as interest, dividends, rental and royalty income, and capital gains, will see a reduction in the total amount that their active income is eligible for the small business tax deduction.

Another difference between corporate tax and personal income tax is when returns must be submitted to the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA). Personal income taxes must be filed by April 30 each year; however, the corporate tax filing deadline depends on when a business’s fiscal year ends.

If your corporation’s tax year ends on the last day of a month, you must file your return by the last day of the sixth month after the end of the tax year.

However, if your corporation’s tax year doesn’t end on the last day of a month, you have until the same day of the sixth month after the end of your tax year to file.

For example, most corporations’ tax year ends on Dec. 31, which means they have until June 30 of the following year to file their return. But, if your corporation’s tax year ends on April 6, your return is due on Oct. 6.

We discuss this topic in more detail in the “Understanding Canada’s Corporate Tax Calendar” section.

Comparing the Different Types of Business Structures in Canada

Although incorporating your business can help reduce your tax burden, it isn’t always the best option for every small business owner. Under some circumstances, sole proprietorship or partnership might be a better choice than creating a corporation, so knowing what each structure entails is important. Here’s a look at the tax implications of all three business structures.

Sole proprietorship

In a sole proprietorship, a single person owns the business, making all major decisions, keeping all profits, and generally taking on the major risks.

A sole proprietorship is easy to set up and dissolve, has low startup costs, and has fewer regulations than other types of structures. With this business structure, the CRA only requires you to file a single tax return, and you declare any profit from the business on your individual income tax return.

As a sole proprietor, the CRA considers the business and owner/operator as the same entity. This means that you’re personally responsible for the business. If a creditor files a claim against the organization, they can go after your business or your personal assets.

In a sole proprietorship, your income is taxed at your personal rate. If the business experiences a bad year, you can deduct the losses from your personal income, which will lower your tax bracket.

Partnership

A partnership is a nonincorporated business between two or more people. A partnership has no legal structure; therefore, partners should draft an agreement that stipulates how the business is structured in terms of revenue, profits, expenses, and liabilities.

This type of business structure is simple to create and dissolve, and it also has low startup costs.

A partnership isn’t required to file a tax return or pay income tax on behalf of the business. Instead, there’s no legal difference between you and the business. As a result, each partner is responsible for filing their own income tax return and claiming the agreed-upon share of the partnership’s profits or losses.

Corporation

A corporation is a formal business arrangement that creates a legal entity separate from the owner.

The act of creating a corporation, or incorporation, offers small business owners the most liability and tax advantages. Because a corporation is technically its own entity, it protects the owner’s personal assets if someone takes legal action against the business.

Corporations can also take advantage of the small business tax deduction, paying a lower tax rate on the first $500,000 of active business income.

With corporations, there can be higher administrative costs due to setup fees and paperwork compared with other types of business structures. Incorporation can be a complex and time-consuming process, so it’s best to enlist the help of specialists who can guide you through the process.

Download The Ultimate Guide to Incorporated Small Business in Canada to learn more about becoming an incorporated small business.

Resources

The Benefits of Incorporating a Business in Canada

A lot of new businesses start as sole proprietorships, mainly because they’re the easiest and least expensive business structure to maintain.

However, many small business owners choose to incorporate as they grow because it offers access to several tax advantages and other benefits that aren’t available to unincorporated entities, including:

Lower tax rates

As mentioned in an earlier section, if your small business or farm operates as a sole proprietorship or partnership, you will pay the personal income tax rate on profits.

Incorporating your farm or business allows you to take advantage of the small business tax deduction and pay a lower tax rate on the first $500,000 of active business income.

An additional tax advantage is that you may be eligible for capital gains exemptions if you decide to sell the corporation in the future.

Deferred personal income tax

Incorporating your business allows you to pay yourself in the most tax-efficient way.

You can pay yourself through a salary, dividends, financial bonuses, or a combination of the three. If the business makes a lot of money in one year, you can leave some funds in the business and defer personal taxes.

If you own shares in the business and want to take advantage of the lifetime capital gains exemption, you must incorporate your business.

Income splitting

Income splitting redistributes income within a family—usually from a spouse in a higher tax bracket to a spouse in a lower tax bracket—to reduce a family’s overall tax bill. Income splitting typically works best when one spouse earns significantly more income than the other, so the tax savings are more significant.

However, the CRA has attribution rules that require individuals to declare income sources, including any income made from investments with savings or capital. This means that any income generated from a gifted investment would be attributed back to the high earner and taxed at a higher rate.

Limited liability

A corporation is considered a separate entity from the shareholders. This means creditors and any legal action are held against the corporation and its assets—not you and your personal assets.

If you own a small business that involves a great deal of risk, incorporating your business could potentially protect you and your personal assets from any unexpected legal or financial issues.

Income control

Incorporated business owners have multiple options for determining the most tax-efficient method of paying themselves.

For example, you may choose to pay yourself a salary, take dividends or bonuses, or customize a combination that fits your tax goals.

Resources in this section:

Benefits of Incorporating a Small Business in Canada

Benefits of Incorporating Your Farm (Lower Taxes)

The Disadvantages of Incorporating Your Business

Although there are many reasons why incorporating is a solid business decision, there are also a few disadvantages to incorporation that you need to be aware of, including:

High costs

Along with initial setup and filing fees, an incorporated business will have ongoing legal and accounting expenses.

More paperwork

There is much more paperwork involved when your business is incorporated. For example, you must submit legal paperwork each year, including an annual return, corporate tax return, and your minute book. In addition, you will need to file a separate tax return to ensure it complies with corporate regulations.

No personal tax credit for losses

If your business loses money during the first few years of operation, those losses stay with the company. You can’t claim the losses on your personal tax return. However, while you can’t write off the accumulated negative earnings, you can carry those losses forward to deduct against the corporation’s future profits.

Resources

Quick Look: How to Prepare Your Corporate Taxes in Canada

As a business owner, filing your corporate taxes correctly is critical. Here’s an at-a-glance look at the steps to follow to ensure your corporation is ready for tax day.

Gather your documentation

Use this list to ensure you have the information and documents you need to file your corporate taxes:

- Company name and address

- Corporate key (i.e., unique business number) from the Canada Revenue Agency

- Names, addresses, and countries of residence for all company shareholders

- Names, addresses, and countries of residence for all authorized corporate signatory shareholders

- All financial statements, including statements of income, balance sheet, and so on, filed with the General Index of Financial Information

- Description of the company's main business functions

- The company’s sources of income, including investment income

- Declaration of shareholders’ shares in other companies and whether your company is legally associated with other companies

- Whether the company conducts business or owns property in other countries or other Canadian provinces

- Any dividends paid or received by the company

Documentation of acquisition or disposal of fixed assets

Many of these documents are included in the minute book the CRA requires every corporation to maintain.

Complete your T2 return

The CRA requires all Canadian businesses to file a T2 tax return, including nonprofits and other tax-exempt organizations and businesses that didn’t generate income during the tax year.

We discuss T2 tax returns in detail in the section “What Is a T2 Corporation Income Tax Return, and Do I Need to File One?” Here are the links you’ll need for the CRA’s tax schedules for corporate taxes.

Know when your tax return is due

Unlike personal tax returns that are due on the same date for everyone, corporate tax filing deadlines are based on your business’s specific year-end date.

See the section “Understanding Canada’s Corporate Tax Calendar” to learn how to determine when your taxes are due.

File your taxes with the CRA

Although you can file your own corporate taxes, keep in mind that Canadian tax laws are complicated and change frequently. Working with a trusted tax specialist can help ensure your tax return is accurate and reflects all of the deductions and credits your business is entitled to. We’ll discuss credits and deductions in depth in later sections

What Is a T2 Corporation Income Tax Return, and Do I Need to File One?

The T2 is a type of corporate income tax return the CRA requires from incorporated businesses each year. This declaration of corporate income is far longer and much more complex than the tax forms individuals and sole proprietorships use.

All corporations, nonprofit organizations, tax-exempt corporations, and inactive corporations are required to file a T2 return—even if there is no tax payable. Businesses can file one of two types of T2 tax returns required by the CRA: the standard T2 Corporation Income Tax Return or, if eligible, the T2 Short Return.

All corporations that report annual gross revenue of more than $1 million are required to file their T2 Corporation Income Tax Return electronically, with the following exceptions:

- Insurance corporations

- Nonresident corporations

- Corporations reporting in functional currency

- Corporations that are considered exempt from tax payable under section 149 of the Income Tax Act

However, this $1 million threshold will be eliminated after 2023, and most corporations will have to file their return electronically regardless of their annual gross revenue, or they’ll face penalties.

The CRA imposes a $1,000 penalty to corporations that are required to file electronically if they fail to comply. That’s why it’s best to work with an experienced tax specialist when filing your T2.

Understanding Nil Corporate Tax Returns

A zero-tax return, also called a nil tax return, is a corporate tax return that reports no income during a certain tax year and, therefore, no tax payable. Nil corporate tax returns are primarily filed by businesses that either didn’t operate during a given year or are reporting a loss.

A CCPC with a loss or a nil net income for income tax purposes is eligible to use the T2 Short Return form to file a nil corporate tax return if it also meets the following criteria:

- It has a permanent establishment in only one province or territory.

- It isn’t claiming any refundable tax credits (other than a refund of installments it paid).

- It didn’t receive or pay out any taxable dividends.

- It is reporting in Canadian currency.

- It doesn’t have an Ontario transitional tax debit.

- It doesn’t have an amount calculated under section 34.2.

Understanding Canada’s Corporate Tax Calendar

In Canada, corporate taxes are reported on an annual basis; however, that year is based on the company’s fiscal period (53 weeks max) rather than the calendar year.

Here are some answers to commonly asked questions about Canada’s corporate tax calendar.

When are corporate taxes due?

Corporate tax returns are due six months after a corporation’s fiscal year-end. If your business is incorporated and you owe taxes, you have up to two months after the end of your tax year to pay off the balance.

However, this guideline carries some exceptions. A CCPC that reports annual business incomes under $500,000 may have up to three months instead of two to pay the balanceif it meets certain criteria.

According to the CRA, when a corporation’s tax year ends on the last day of a month, it must file the return by the last day of the sixth month after the end of its tax year. When the last day of the tax year isn’t on the last day of a month, it must file the return by the same day of the sixth month following the end of the tax year.

So, for example, if your tax year ends on Dec. 31, your filing deadline is June 30; if it ends on Sept. 23, your filing deadline is March 23.

If your business is owed a tax refund, you must file a return no later than three years after the end of a tax year to receive it.

Will I be penalized if I file my corporate tax return late?

Yes, if you owe taxes and you file your tax return late, you will be charged a late filing penalty. This penalty is 5 percent of the balance you owe plus 1 percent of the total balance for each full month your return is late, up to a maximum of 12 months. You will also be charged daily interest on any outstanding tax.

However, if you don’t pay your annual corporate taxes within the allotted time over multiple years, this penalty can increase to 10 percent plus 2 percent for each month your return is late, up to a maximum of 20 months.

The CRA will also assess a penalty if a corporation makes a false statement or omission—intentionally or negligently—on a return. The penalty is the greater of either $100 or 50 percent of the amount of understated tax.

Remember that filing corporate taxes is extremely complex, and the penalties for late and incorrect filing can add up. Working with a tax specialist will help you navigate Canada’s elaborate tax system, ensure you are filing correctly, and make the process much less stressful.

Corporate Income Tax Rates for Small Businesses in Canada

In order to pay taxes at the corporate rate rather than the personal rate, the money you are paying taxes on must stay with the business and not be used for personal expenses, such as a home mortgage or personal car payment.

If corporate income is used for personal expenses, the corporation can’t deduct those expenses. In addition, the money must be reported on your personal tax return as a shareholder benefit since it wasn’t received or taxed as a salary, bonus, or shareholder dividend.

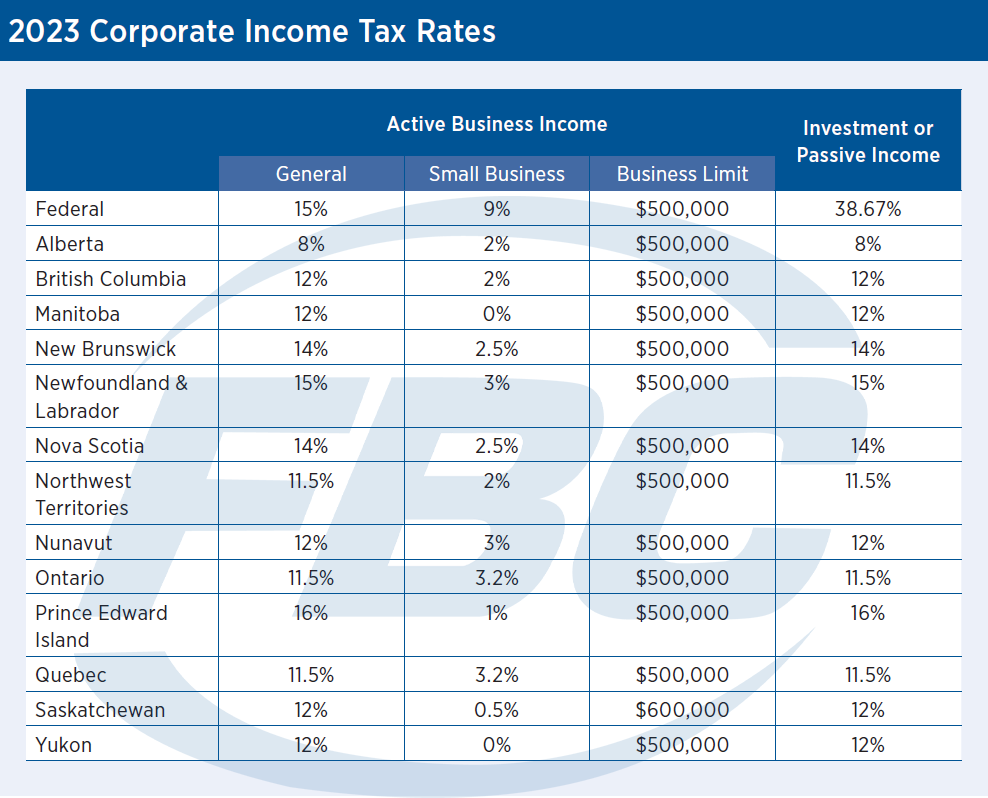

The tax rates for incorporated small businesses in Canada vary depending on income earned, where the business is located, and whether the business qualifies for any tax credits.

There are two levels of tax rates in Canada, often referred to as the lower tax rate and the higher tax rate, which allows smaller corporations to keep more of their earnings.

The thresholds are based on business limits that are set by the federal government or by individual provinces and territories. At the federal level, the lower tax rate is paid on the first $500,000 of a business’s taxable income, and the higher tax rate kicks in when the company earns more than $500,000 in taxable income. (See the table below for business limits broken out by province and territory.)

Qualified CCPCs can claim the small business deduction (SBD) to reduce the Part I tax they are required to pay, which is calculated using the following information from the T2 Corporation Income Tax Return:

The SBD is 19 percent of whichever of the following amounts is less:

- The income from active business carried on in Canada (line 400)

- The taxable income (line 405)

- The business limit (line 410)

- The amount on line 428, which is the reduced business limit on line 426, from which you deduct the amount of the business limit you assigned under subsection 125(3.2)

So, at the federal level, the basic rate of Part I tax is 38 percent of your taxable income, which is reduced to 28 percent after the federal tax abatement. The federal tax abatement provides a 10 percent reduction in the federal basic rate that allows provinces and territories to impose their own income tax rates, as shown in the table below.

After applying the SBD, many CCPCs pay a 9 percent net tax rate, while non-CCPCs and larger corporations that aren’t eligible for the SBD pay 15 percent.

The federal tax rate and the provincial tax rate are applied separately to your business’s taxable income, so your total tax liability is the sum of both the federal and provincial/territorial taxes after applicable adjustments.

Corporate Tax Rates and Business Limits

Remember: Tax laws can change, so it's always a good idea to consult with a tax specialist or visit the CRA website for the most up-to-date information.

Resources

Tax Implications of Active Income, Passive Income, and Personal Services Businesses

Canadian corporations are taxed differently on active versus passive income. It’s important to understand the difference so you can file correctly and avoid penalties.

Active and passive business income

According to the CRA, active business income is “income earned from a business source, including any income incidental to the business.” This means income earned from actively doing something to generate the income from a business source.

Passive income refers to income generated through nonactive sources, such as interest, dividends, rental and royalty income, and capital gains.

Qualified CCPCs can claim the SBD on active business income up to a maximum of $500,000 annually; however, the SBD doesn’t apply to a corporation’s passive income.

It’s critical for corporations to accurately classify active and passive income because the CRA is vigilant about identifying misallocated passive income and is more likely to audit a business it feels has filed incorrectly.

Personal services business

CCPCs must also be cognizant of the tax rules governing personal services businesses (PSBs). The CRA defines a PSB as “a business that a corporation carries on to provide services to another entity (such as a person or a partnership) that an officer or employee of that entity would usually perform.”

An example of a PSB is a delivery driver who incorporates their delivery services but only provides those services to a single company. In other words, you are considered a personal services business if you would be performing the same work as an employee of the company if you hadn’t incorporated your business services.

PSBs aren’t eligible for the general tax rate reduction or the SBD and must pay the full federal and provincial corporate tax rates on all taxable income plus an additional 5 percent.

Resources in this section:

Tax Increases Affect Passive Income for Private Corporations

Why Your Incorporated Business Needs a Minute Book

A minute book is a collection of corporate and legal documents that track an incorporated company’s activities and decisions, such as dividend payouts; issuance of shares, loans, and mortgages; shareholder agreements; major financial transactions; and payment of bonuses to officers and directors.

Keeping a minute book is a legal requirement for all Canadian incorporated businesses, and your business’s minute book can be subject to government review to ensure your business is in compliance.

Minute books essentially create a paper trail of payments the corporation makes, which provides proof that your corporation has complied with all mandatory government filings, including your annual return, and can prevent disputes over the issuance of shares, dividends, and shareholder loans.

Failing to maintain a minute book can have serious consequences, including:

- Jeopardizing or slowing down any potential future sale or transfer of your business due to lengthy and expensive legal delays

- Paying higher taxes, tax penalties, and fines on the shareholder dividends your corporation has paid out because they weren't properly recorded

What your minute book should include

To ensure your minute book meets CRA requirements, be sure to include the following information and any relevant documentation:

- Articles of incorporation

- Board of directors register

- Officers register

- Bylaws and their amendments

- Resolutions and annual shareholder meeting minutes

- Share certificates and share transfer registers

- Changes in share structure (including the number of shares)

- Directors, officers, and shareholder registers

- Notices that have been filed, including change of registered office address and changes to company directors

- Shareholder agreements

- Details of the corporation’s quarterly and annual financial statements

- Dividends dispersed to owners

- Management fees or bonuses

- Filing periods

Resources

Filing Your Corporation’s Annual Return

In addition to filing a T2 Corporation Income Tax Return and maintaining a minute book, Canadian corporations of every size are required to file an annual return if their legal status with Corporations Canada is “active.”

The purpose of the annual return is to help keep the public-facing Corporations Canada database of federal business corporations current so investors, consumers, financial institutions, and other interested parties can make informed decisions about corporations.

Missed and Misunderstood Tax Credits for Incorporated Businesses

When you’re a small business owner, any amount of tax savings helps, so it’s important to make sure you are taking advantage of all available tax credits.

Tax credits are different from tax deductions—which we will cover in the next section—in that credits reduce your final tax bill and may make you eligible for a refund, while deductions lower the amount of income your business is taxed on when you file. In short:

- Tax credits reduce the amount of tax you pay on your taxable income.

- Tax deductions reduce your taxable income.

Tax credits generally reduce the amount of tax you owe on a dollar-for-dollar basis. For example, if your total tax credits combined equal $100, you would subtract $100 from your total tax owed.

Let’s take a look at some of the different types of tax credits for incorporated small businesses in Canada.

Investment tax credits

Small business owners may be eligible to claim one of the following investment tax credits if any of the following applies:

- You bought certain new buildings, machinery, or equipment, and they were used in certain areas of Canada in qualifying activities such as farming, fishing, logging, manufacturing, or processing. (See Atlantic investment tax credit.)

- You have done work that qualifies for scientific research and experimental development tax incentives. (See Scientific research and experimental development tax incentive.)

- You employ an eligible apprentice and want to claim an apprenticeship job creation tax credit.

- You have unclaimed credits earned in the last 10 years.

If you qualified for investment tax credits but didn’t claim them, you can carry forward credits for up to 20 years. You can also carry back the credit you earn for up to three years. You may also be able to claim a refund of your unused investment tax credits.

There are eligibility rules and requirements that you must meet before you can claim investment tax credits, so consult a tax specialist to ensure you’re following the rules.

Input tax credit

If you have a registered goods and services tax (GST) or harmonized sales tax (HST) number, you may be eligible to recover GST/HST paid or payable on purchases and expenses related to your small business by claiming input tax credits.

To claim this credit, keep track of GST/HST paid on all eligible small business expenses so that you can claim them when you file your GST/HST return. Be sure to keep your receipts should you be required to back up your claims.

What expenses are and are not eligible for input tax credits?

To claim an input tax credit, each purchase and expense must be reasonably related to your small business and for consumption, use, or supply during the course of doing business.

The CRA lists the following expenses as eligible for input tax credits:

- Business-use-of-home expenses

- Delivery and freight charges

- Fuel costs

- Legal, accounting, and other professional fees

- Maintenance and repairs

- Meals and entertainment (allowable part only)

- Motor vehicle expenses

- Office expenses

- Rent

- Telephone and utilities

- Travel

Input tax credits cannot be claimed on the following expenses:

- Certain capital property

- Taxable supplies of property and services bought or imported to make exempt supplies of property and services

- Membership fees or dues to any club whose main purpose is to provide recreation, dining, or sporting facilities (including fitness clubs, golf clubs, and hunting and fishing clubs) unless you acquire the memberships to resell in the course of your business

- Property or services you bought or imported for your personal consumption, use, or enjoyment

Tax Deductions for Incorporated Businesses

If you’re a small business owner, you understand how quickly business expenses can add up. Luckily, there are many available tax write-offs you can use to reduce your overall tax bill.

Small business tax deductions are allowable expenses that help lower your taxable income, which is different from small business tax credits that directly reduce the final tax amount you owe to the CRA.

Here are some of the common tax deductions available to incorporated businesses in Canada, though some stipulations apply:

- Accounting and legal fees

- Advertising and promotional expenses

- Bad debt

- Business taxes, licenses, and memberships

- Business-use-of-home expenses

- Depreciation expenses

- Employee salaries and benefits

- Interest and bank charges

- Insurance premiums

- Meals and entertainment

- Office expenses

- Rent

- Repairs and maintenance

- Tools and equipment

- Vehicle expenses

If you’re unsure whether an expense qualifies as a tax deduction, remember that deductible expenses are those that are reasonably required to make the business operational, keep it running, or generate income.

One exception to this guideline is charitable donations. Although unincorporated small businesses in Canada can claim a tax credit for charitable donations, they are considered a Division C tax deduction for incorporated businesses. See the CRA website for qualified donations and deduction limits.

Paying Yourself from Your Corporation: Talk to a Tax Expert, but Have a Basic Understanding

As the owner of an incorporated business, there are three ways you can take money out of the corporation:

- Pay yourself a salary.

- Pay yourself dividends.

- Take out a shareholder loan.

Paying yourself salary, dividends, or a combination of both is considered personal compensation, so it’s important to understand the tax implications of each method.

A shareholder loan is another option for taking money out of a corporation; however, the loan isn’t considered personal compensation, so the funds are taxed differently. We’ll discuss the details of shareholder loans in the next section.

Here, we’ll look at the differences between paying yourself a salary versus taking dividends and how each option affects your tax responsibilities and your retirement income planning strategy.

Should I pay myself a business salary?

Even if you are the only employee of the company, when you decide to draw a salary, you will need to register a payroll account with the CRA, and you will receive a T4 Statement of Remuneration Paid slip.

Each time you pay yourself, you are required to withhold and remit payroll taxes to the CRA and make mandatory contributions to the CPP.

If your net income is more than $3,500, your CPP contribution will be twice that of an employee because you are paying both the employer’s share and the employee’s, though the employer portion is tax-deductible.

Salary and wages are considered employment income, so they are taxed at the personal income tax rate, which is higher than the corporate tax rate. However, your salary is considered a business expense for your corporation, which lowers the company’s taxable income and, therefore, reduces taxes the corporation owes.

Being a salaried employee of the company has several benefits, including a stable and predictable income, which can help you qualify for loans and mortgages, and the ability to contribute to the CPP and a Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP), which can help you financially prepare for retirement.

But, if you take a salary, you will pay more in taxes, and you will have to invest time and resources into processing payroll and maintaining compliance with employment standards and regulations.

Should I pay myself dividends?

Dividends are payments that a corporation makes to its shareholders from after-tax profits. Unlike salaries and wages, dividends aren’t considered employment income, so there’s no need to register a payroll account with the CRA or pay CPP. Employment premiums and dividend payments are eligible for a dividend deduction, so they are taxed at a lower rate than employment income.

Lower personal tax liability is one of the major benefits of taking dividends over a salary, but you also gain the flexibility of deciding when and how much to pay yourself in dividends, which gives you even more control over tax planning.

Taking dividends can have a negative impact on your retirement income planning because you won’t accumulate CPP benefits, and dividend income doesn’t generate RRSP room.

Relying solely on dividends can also lower your reported personal income, which can affect your ability to qualify for loans.

The verdict?

Paying yourself a salary is a good option for business owners who want the peace of mind of a steady income or who want to take advantage of the CPP and an RRSP as part of their retirement income planning strategy. Taking dividends is an excellent way to pay yourself and control your tax liability.

Ideally, a combination of both strategies will help you meet your financial planning goals; talk to a tax planning specialist to learn how to maximize both your personal income and your tax advantages.

Resources in this section:

Salary or Dividends: Which One Is Right for Me?

Shareholder Loans

A third option for taking money out of your corporation is a shareholder loan. Unlike salary and dividends, these loans aren’t designated as personal compensation, and the funds must be repaid following agreed-on loan repayment rules.

Stakeholder loans originate from the corporation, so the money hasn’t been taxed at a personal level. As long as the money is repaid before the end of the corporation’s next fiscal year, you don’t have to pay personal tax on the borrowed funds. However, if you fail to meet this deadline, the loan must be reported in the shareholder’s personal income tax filing.

There are two types of shareholder loans: “due from shareholder” loans and “due to shareholder” loans.

Due from shareholder

A loan is considered “due from shareholder” if corporate funds are borrowed for personal purposes and personal tax hasn’t been paid on those amounts. This type of shareholder loan is subject to special rules, such as requiring repayment to the corporation within a year.

Due to shareholder

“Due to shareholder” loans pay for company expenses using personal funds you loan to the company. This is considered an owner contribution and is reflected on the balance sheet as a debt owed (liability) by the company, and the company will need to repay the owner at some point.

Tax implications of shareholder loans

The most important tax implication is the shareholder loan repayment rule: The loan amount won’t be included in your personal taxable income if you repay the loan within one year of the end of the corporation’s fiscal year. If you don’t repay the loan within that time, you must include the unpaid amount in your taxable income and pay income tax on it.

If you weren’t charged an interest rate on the loan, you must add interest rates equal to the prescribed rate to your taxable income. The prescribed rate is currently 5 percent but is subject to revision every quarter.

Resources

Selling Your Incorporated Business: Start Succession Planning Early

Succession planning is the process of creating a strategy for the transfer of ownership of your corporation when you retire, if you become disabled or die, or if you are simply ready to sell.

There are a lot of legal and tax factors to consider during succession planning, so it’s important to start working with a lawyer, accountant, financial advisor, and succession planning specialist early in the process to ensure you have a solid plan established well in advance of needing to implement it.

There are two main options for selling an incorporated business in Canada—share sale and asset sale, each with specific capital gains and other tax requirements.

Share sale

Incorporated businesses can sell the corporate shares, giving the buyer control of the business and all of its assets, liabilities, and debts.

If certain conditions are met, the shares might qualify for a lifetime capital gains exemption (LCGE), which means the seller doesn’t pay any tax on capital gains up to the specified LCGE amount.

The LCGE is indexed to inflation and increases every year, so, for example, if you sell shares of a qualifying Canadian business in 2023, the LCGE is $971,190, up from $913,630 in 2022. However, because only one-half of realized capital gains is taxable, your cumulative capital gains deduction is $485,595, or half of an LCGE of $971,190.

Let’s look at an example of the LCGE in action:

Shares of a small business corporation make the seller a $2 million profit. Without the LCGE, the seller would have to pay taxes on half of these capital gains, or $1 million. However, because the 2023 LCGE allows the seller to subtract $971,190 from the profits, the seller only pays taxes on $514,405 ($2 million - $971,190) X 0.5 rather than on $1 million.

Asset sale

An asset sale is a bit more complicated than a share sale. During an asset sale, all of the assets your business owns are sold. This includes tangible goods, such as land, equipment, buildings, cash, investments, and inventory, and intangible goods, such as client lists, goodwill, patents, copyrights, and trademarks.

Unlike a share sale, in which everything passes to the new owner, an asset sale allows you to negotiate the selling price and choose which assets to sell. For example, you may choose to keep your business name.

Capital gains on asset sales aren’t eligible for the LCGE, and taxable income from an asset sale can include capital gains on other capital properties and capital gains on goodwill. Because you are only selling your company’s assets, you may still be responsible for any liabilities or debts.

Note: If you are a sole proprietor or in a partnership, an asset sale is the only option available to you.

Resources

Is It Time for Professional Help with Your Tax Planning?

FBC was founded on the belief that Canadian businesses should receive every tax benefit they qualify for. More than 70 years later, our focus continues to be the financial peace of mind of our Canadian farmers and small business owners.

This real-world experience means we know what tax-saving strategies will maximize write-offs and minimize your corporation's tax bill.

In fact, FBC helps Canadian business owners save more than $42 million a year. Let’s find out how we can help you.

Click the link below to book a free 15-minute consultation.

Download a PDF version of this guide by filling out the form